- Home

- Lygia Day Penaflor

Unscripted Joss Byrd Page 2

Unscripted Joss Byrd Read online

Page 2

I press my head deep into my pillow. Tatum’s close-up is all tears and freckles.

“She’s so scrappy. That’s what everybody sees in you.”

That’s why you have to work as much as you can …

“That’s why you have to work as much as you can while it’s still cute to be scrappy. We have to ride this wave as long as possible.”

Just ride it and ride it and ride it …

“Just ride it and ride it and ride it.”

Doris says that puberty can be the end of a child actor. Girls who stay petite and flat can play young parts for a very long time. But if you’ve seen my mother, who’s tall and definitely not flat, you know that probably won’t happen for me.

The laptop settles on my mother’s stomach as she stretches her legs. “Tatum was lucky. It was easy for her to transition to teen roles because she grew up beautiful. But you might, you might not. If we save every penny now you won’t have to worry about it either way.”

I’ll worry no matter what. Savings or no savings, if I have to grow up at all, I’d like to grow up beautiful.

“And if you work enough now, you definitely won’t have to struggle when you’re my age. Look at those eyes … God, that Tatum…”

After I’d studied the movie too many times to count, Doris told me that Paper Moon could’ve been shot in color, but it was made in black and white on purpose, to be more believable. Who knew? That’s another thing I learned from Paper Moon besides how to be scrappy: you can get away with anything if you do it on purpose. The way I figure it, as long as I keep a straight face, people will believe that I’m a real actor, when really all I am is a kid who wanted to skip school that first day.

“Nobody ever pushed me. Nobody ever thought I was worth pushing. You have something, Joss. You really do,” Viva says, adding new words to her comments. “And the fact that you have these opportunities … well, who would’ve imagined?” She’s braiding my hair like she used to when I was little. “I just don’t want you to waste all of this. I wish you could understand that.” She lets the braid loose and combs through it with her fingers. “Life’s hard enough when you haven’t got a talent. I should know. I don’t want your life to be hard.”

When I take a long, deep breath, I can make out the sweet smell of my mother’s lotion hiding beneath her stale layer of smoke. Tatum singing is the last thing I hear before I fall asleep. Her voice almost convinces me that everything will be just grand.

“Keep your sunny side up, up. Hide the side that gets blue!”

2

“I’m so happy to meet you, Joss. I’ve watched Hit the Road a dozen times. You’re so good in it. So good.” Terrance Rivenbach, the famous director, hugs me with both arms. “Can I tell you a secret?” He has twinkly eyes; that’s my favorite kind of face. All at once I’m nervous. I don’t know how to talk to someone who’s more handsome in person than he is on the Internet. “You’re the only Norah I want.” He winks.

Terrance’s office is full of boxes. All that’s out are file folders, pictures of his family, and a coffeemaker. “Let’s sit down, Joss. Sorry. This is a new building. We’re all just getting settled.” We walk around the boxes to get to the chairs near the window. “How do you like LA?” He smiles kindly and hands me a warm bottle of water from a box.

I uncap the bottle but don’t drink. “Fine.”

“It’s a long way from Tyrone, Pennsylvania. Think you’ll want to come live here someday?” He tilts his head toward the window. “You’re getting awfully busy filming movies.”

“I guess.” I peel the label off my water. I should tell him that it’s our goal—Viva’s and mine—to live in Beverly Hills. Our favorite houses are the ones with ivy up the sides. You can tell they’ve stood there since what Viva calls the Golden Age of Hollywood, which was when “darn” was a curse, people kept their clothes on, and the camera faded after kissing. Even if you just moved into your ivy house, you can pretend that you’ve had money since the Golden Age. But I don’t say any of that to Terrance.

“How do you like acting?”

It’s the one thing, the only thing that makes me special, I think. “It’s good,” I say. I’m failing the interview already. Damn.

* * *

Every day in Montauk the cast-and-crew van shuttles us between the Beachcomber and our production basecamp and our filming location. This morning I have rehearsal first. Then I’ll tutor for a while before we shoot. Our driver is following the handmade TO SET signs that lead us through narrower and narrower streets of tiny beach houses. When we pull up to what’s supposed to be TJ and Norah’s house, the crew is hauling equipment to the backyard. I’m embarrassed straight off by this rickety place with a dirt driveway because everyone’s been saying that I’m perfect for the part of Norah. How can they tell I really am a dirt-driveway kid? (That is, if I had a driveway.) And I’m also embarrassed for Terrance because the character TJ is based on him as a kid; The Locals is about him, his actual sister, Norah, his actual evil stepdad, and his actual dumpy house. Why would somebody who’s rich want the world to know that he used to be poor?

“Uh-oh! Here comes trouble!” In the backyard, a happy Terrance holds his arms open. “Look out, Montauk!” He squeezes me so tight—the exact way he hugged me when we first met—that I can smell his aftershave and his morning coffee.

I squeeze him right back. “Morning, Terrance.”

“When are you going to start calling me TJ?” he asks. But I can’t call him that. TJ is a kid’s name—a boy with a rainbow lollipop.

If you’ve ever met Terrance Rivenbach you’d never guess he grew up in a shack. I can tell you one thing: the minute Viva and me dig our way out of the hole we’re in, we aren’t gonna look back. We’re in what my mother calls a “steaming pile of debt without a shovel.” It’s stupid that we’re in debt because we haven’t got anything good. I mean it—nothing. For such a long time, I’ve wanted this pair of chunky headphones that I can use on plane rides. But all Viva can say is, “What do you need those for? They’re ridiculous.” I want them because they would cancel out noise—her voice, for example—when I need my privacy.

Thanks to Viva’s ex-boyfriend, all we do have are empty plots of land because his master plan to build upscale beauty salons was a bust. We also have a hole in our bank account where there used to be my movie money. When my mother’s not screwing it up, I don’t mind earning money for us. I really don’t. I like being useful. It’s called being the breadwinner. But that’s what made losing my movie money feel ten times worse.

“Take a look at these.” Terrance hands me a sheet of pictures from my photo shoot the other day. Me and Chris were made up to look like an old photo of Terrance and his sister when they were little. “Here’s the original. And here’s you two,” he says, holding both photos.

“We look exactly like you!”

In the original, Terrance and Norah are in the middle of the street. He’s straddling his bicycle, and Norah, wearing rainbow shorts, is pinching her elbow and staring straight into the camera with a bubble wand between her teeth. In our new photo, me and Chris are positioned just the same.

“Amazing, isn’t it?” Terrance points from his picture to mine. “This is going to be our poster.”

I look over at Chris. He’s by the snack table reading today’s call sheet, which tells the scenes we’re filming and in what order. “Hey, Chris! Cool, huh?”

“I know, right?” There’s dirt on his palm when he lifts his hand. Judging from the scrapes on Chris’s elbows and the smudges on his face, it looks like he’s been rehearsing already.

Rodney, the actor who plays our evil stepdad, keeps staring at me from inside the screen door. I smile at him, only because I’m used to being polite. But there’s no charming Rodney.

“You know he likes to stay in character.” Terrance slips the photos into a big Ziploc bag. “Just let him be.”

Rodney likes to stay in character so much that his name isn’t even Rodney

. It’s Tom Garrett. But we aren’t supposed to use that name at all; it even says “Rodney” on call sheets and memos where the rest of us have our real names.

He might only be acting, but Rodney’s still plenty scary. When my mother told me The Locals was about a girl who gets abused by her stepdad, I said, “No way. No how.” I didn’t want some strange man acting dirty with me. Good thing Viva felt the same. She said everybody draws the line somewhere. Plus, she figured a kid like me with a few movies in my pocket should have a say-so in my own career. So she and Doris fixed my contract so I wouldn’t have to do any pervy scenes. That was a major relief, especially the second I got a look at Rodney. According to Google, he used to be a pro football player. That explains his giant hands and his beer gut. I think that when athletes stop playing their muscles melt into their bellies.

Anyway, Viva said that the contract would protect me from “content of a sexual or violent nature as deemed by the minor’s parent and management.” She also told me that for once, I’d get to work with other kids on this movie. That sealed the deal for me, even if there is a pervy stepdad.

Terrance walks me over to a tall, fat tree that shades half the backyard. “Joss, for this scene, I want you to sit up here in this big old tree.”

“Yes!” I pat the tree like an old friend, excited to spend the day in it. It’s a heavy-duty scene, but more so for Chris. For me, it’ll be fun being up in the tree.

“You’ll watch TJ and Buzz drill the rungs into the trunk from up here,” he says. “And we’ll do some nice close-ups on you right before Chris gets roughed up.”

Chris is roughed up already. The medic is cleaning him up with alcohol pads.

“We’ll put some padding up here to make it comfortable,” Terrance says as I pull myself up by the low branches.

“Whoa, not yet.” He grabs hold of my arm. “Let’s save the climb for later. You’re not allowed to break your neck until after we wrap.”

“But it’s easy.” I look up through the flat leaves rustling above. “It’s not even that high.”

“It’s high enough.”

“Joss, you’re so lucky you get to be up in the tree!” says Jericho. He plays Buzz, TJ’s best friend. I thought the hair department was going to give Jericho a buzz cut, but I guess that’s not where the name comes from; he’s still shaggy as ever. “Look what I get! A saw!” Jericho lifts a rusty saw from against the tree and holds it for me to see.

“Hey, hey! Put it down!” Terrance yells, getting serious. “You have to get instructions on that first. There was a reason for the safety memo this morning. No props until I say so. If there’s any fooling around on this set, I’ll shut it down. That goes for all of you. Clear?”

“Aye, aye, Cap’n.” Jericho lowers the saw back to the ground.

I don’t get Jericho. The Locals is only his first movie, but he fools around all the time as if he’s been acting forever. I’m never that comfortable on set. My theory is he’s relaxed because he’s a hobby actor. That’s what I call a kid who’s the opposite of a breadwinner—a kid who works for fun, not for money, which must be way less stressful. While I bring home the bacon, hobby actors bring home stories about famous people to tell around the dinner table. I can tell a hobby actor from a mile away. I’ve noticed Jericho’s dad working with color-coded graphs on his laptop and heard him make business calls on “Tokyo Time.” He also wears a watch that can go underwater. Jericho said so.

“For now, just play with the dialogue for a bit before I see it,” Terrance says.

Viva is standing off to the side with the executive producer, Peter Bustamante. After three movies, I still don’t know what a producer does. It’s too late to ask, so I just pretend to know. But I’m plenty interested in any job where you walk around acting like the boss but never actually do anything. Peter doesn’t work any equipment or even carry a script.

Viva gives me a wave. She likes to remind big-deal people that she’s my mother. I wave back. I like to remind big-deal people that I’m a good daughter; Doris says that being pleasing on set is as important as being talented.

Tonight will be a fancy dinner night, for sure; Viva looks in a good mood. But before I can say Lobster Roll, Terrance passes me a green script. My stomach drops like a water balloon.

“What is this?” I ask, trying to give the papers back.

“The green revision,” Terrance says, handing the boys the same. “Rewritten as of five a.m. I was up all night, so let’s just get through this day, everybody.”

I scan through it for anything familiar, but everything looks different from the yellow pages I know. When I turn around for my mother, she’s at the craft service table slipping granola bars into her purse. She doesn’t even eat granola bars. There’s half a dozen already in our hotel room.

“Read through it a couple of times together,” Terrance says. “Just get used to the changes while I check the camera. Then I’ll take you through the blocking.”

“So … it looks like I start,” Jericho says, as if the new script is no big deal. “Okay, cool.”

Chris gives the green copy a quick look. Then he nods, ready just like that.

But I’m lost before we even begin. When Doris first sent me the script it was blue. Then when we started shooting it was pink and then yellow. I studied pink for weeks before I had to delete it from my brain. Now I’m ready for yellow. I know yellow. I can do yellow. But green?

“Okay…” Jericho clears his throat and reads, “I can’t believe you’re gonna have your own crow’s nest. Why didn’t we think of this before? This is genius.”

Chris reads next, as casual and cool as always. “All we’ll have to do is climb up here every morning, and we’ll be able to see right away how the waves are. No more trekking our boards all the way down to the beach at six in the morning when the water’s flat.”

“I’m gonna be over here every day!” Jericho says in his raspy voice.

Around me, set decorators are stomping around laying down branches and tools, and production assistants are laughing into their walkie-talkies. Viva is on her phone now, shrugging and talking with her hands.

Jericho nudges me. “Joss, it’s your turn…”

At school, my teacher gives me “extended time” for tests and quizzes. But on set there’s no such thing as “extended time.” There’s only now. I track the page with my finger and search for an easy word that can help me find my place …

… nest …

we …

waves …

The boys are staring and breathing. I can hear the air through their nostrils. This is worse than school. If I don’t say the right words, the boys will find out. Then the crew will find out. Then Terrance will find out.

* * *

“What do you like the most about acting?” Terrance asks. His T-shirt is creased from being neatly folded. I bet he’s got a closet of these, perfectly stacked.

“Anything at all?” he asks, turning his palms up. “What do you like about being on set?”

“Uh…” Finally, I peer up at him—at my favorite kind of face. “Not being at school?”

He laughs with his whole chest. I can’t tell if I’m funny to him in a good way or bad, so in a hurry, I think of something to add.

“I mean, I like not having to be me all the time,” I say before he counts me out. “I like being somebody else.”

“Why?” He leans forward and then away as if he’s trying to reel something out of me.

“I don’t know,” I say. But I do. I’ve known since the first time I set foot on a set. So I force myself to tell him because I didn’t fly all the way to LA for palm trees, and I can tell that he’s waiting for some magic words to let him know that I’m really the one. “It’s not always fun, I guess … to be me.”

Terrance isn’t laughing now. Instead, he’s looking at me as if I really am his sister when she was young and he was young and we’re meeting in a time-machine family reunion.

“Listen, Joss.

I’m going to film a movie in a studio in Brooklyn and then I’m shooting the rest on Long Island where I grew up. How would you like to visit my hometown?” he asks.

I smile even though I don’t know what his hometown is like. “Okay.”

“I’ll take you to see Montauk Lighthouse.”

“Can we climb up it?”

“You bet, kiddo.” He taps my leg. “On my set you can do whatever you want.”

* * *

The words bunch together on the page, one on top of the other. I squint. I hold them close and pull them far. I turn them sideways. But my brain won’t straighten them. When I start to shake, so does the script. If people find out, they won’t hire me anymore. They’ll cast smart girls who can learn on the spot. Everyone is replaceable. Doris says so, even the “next Tatum O’Neal.”

“You’re here.” Jericho points at the name Norah.

“I know where I am!” I drop my trembling hands.

“Sorry, I was just trying to help.” Jericho raises his eyebrows. “Jeez.”

“I don’t need help,” I snap and stare at Jericho’s goofy T-shirt of a hotdog chasing a bun. The shirt isn’t from wardrobe. It’s his own. He’s a stupid-shirt wearer.

Jericho lifts his script. “Great, then let’s keep going.”

“What are you, the director?” I ask, snottier than I ever thought I could be. It’s all I can think of to do. Stall. Pick a fight.

Benji, the production assistant in charge of us kids, is making his way over to us.

“You guys. Quit it,” Chris says, through his teeth. “Benji’s coming.”

“Didn’t you know, Chris?” I’ve started something I can’t stop. “It’s only his first movie, but Jericho’s the director now.” I sound terrible. I don’t want the boys to hate me, Chris especially. But so long as I’m yelling, I’m not rehearsing.

“If I was the director, I wouldn’t let you act like a brat just because you’re Joss Byrd,” Jericho answers, even louder than me.

“Cool it, Jericho. Leave her alone,” Chris says. “She’s just a little kid.”

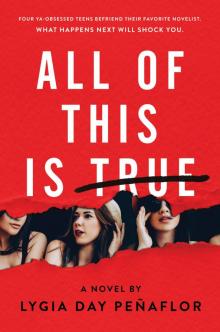

All of This Is True

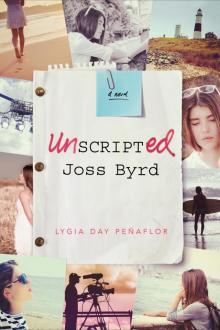

All of This Is True Unscripted Joss Byrd

Unscripted Joss Byrd