- Home

- Lygia Day Penaflor

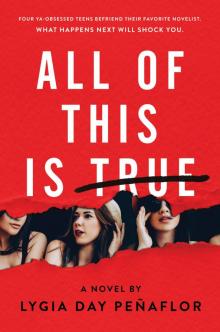

All of This Is True Page 2

All of This Is True Read online

Page 2

Perfect crowd: 12 other people—some our age, others older. Very intimate, like seeing Ed Sheeran at Artists Den. (Gaah! Note to self: Must rewatch the concert video. I’ve missed you, Ed, my favorite ginger.) Here at the Witches Brew we are the truest of the true Fatima Ro fans. And the four of us have been—wait for it—invited!

Fatima: oversized white linen shirt over jean miniskirt, loosely laced Tretorn sneakers, sans socks. Smoky eye makeup. Pale cheeks. Bare lips. Messy hair.

Why can’t I look that glam with half my makeup and bedhead? I’d look like an asylum escapee.

Fatima is ordering green tea. I’ve heard that it has magical properties.

Note: start drinking green tea.

Fatima welcomes the crowd, thanks us for coming. She comments on how cute the café is. She’s never been here before either. Hey, maybe she’ll become a regular and I’ll become a regular and I’ll see her here from time to time. We’ll be on a “Hey, how are you?” basis. How cool would that be?

Jonah (rude boy) is playing with his phone. I jab him with my umbrella.

Undertow book talk with Fatima Ro begins NOW:

First draft written over six months at a feverish pace after her mother passed away, very little sleep, very little to eat, limited communication, virtually unreachable other than by landline. The internet did not even exist, as far as she was concerned. Family and friends thought she was grieving, which she was, of course, but she was “not grieving in stillness” but “grieving with ferocity.”

“Grieving with ferocity.”

Her mother was her grounding force. Her mother was common sense and hard work anchored in reality. Without her, Fatima felt detached from Earth, set in a sudden spiral. As a child, Fatima had too much imagination, was too distractible, too restless. But it was always okay for her to be who she was because her mother kept her tethered to the ground by one toe. When her mother died, Undertow was a desperate way to hold on to her mother’s love, so that it wouldn’t float away forever.

The title, Undertow, existed in her consciousness even before she began writing, because she felt as if she were trapped inside one.

UNDERTOW: the underlying emotion

UNDERTOW: rip current, underlying current, force in opposition

Writing Undertow was the most difficult thing she has ever experienced because it was her grieving process. By writing the character of “Lara,” Fatima was able to drown in loss, feel loss in its deepest depths. She doesn’t know how she would’ve grieved without this place to do it.

Place = the mental state of being “Lara” and writing Undertow.

Revision was very much a swimming to the surface—a period of pushing and fighting to propel back into the world—emotionally, physically.

[Fatima is watching me as I’m taking notes. I’m now self-conscious about taking notes. I’m uncomfortably aware of my hands and my fingers and my shoulders and wrinkling my forehead the way bad actors do to fake that they are taking notes about Undertow when Fatima is watching.]

Losing her mother was transformative at 20 because it marked an inevitable transformation from child to adult. As a child she was so carefree, but when her mother died, she suddenly felt old. Fatima chose to write Lara as age 17 because that’s how old Fatima was when her mother got sick.

Revision of her manuscript was torturous in a different way—it meant revisiting her loss again and again. In shedding the manuscript (from 120k to 80k) there was an emergence of her new self and seeing her own grief from a different perspective each time she reread it. But she fought against the change so furiously at times that revising Undertow became so painful she had to put it away for lengths at a time—weeks, and, for a spell or two, months.

In the end, she had this completed manuscript. She had printed it out and couldn’t believe the weight of it, literally, the weight of its pages. She kept marveling at its weight in actual pounds; she would estimate it, compare it to other objects around the house:

These papers are heavier than this box of tissues.

These papers are lighter than this boot.

< carton of milk

> picture frame

> shampoo bottle

< Bible

Over and over, no matter where she went, she would think about the weight of the manuscript because she was amazed that her grief had literal, physical weight. Grief could be measured in pounds.

“Grief could be MEASURED IN POUNDS!”

She became obsessed with finding out exactly how many pounds.

[Am I really hearing all of this right now? How is this not being filmed and documented for future generations? Even Jonah is listening, balancing a spoon on two fingers. I think he’s weighing.]

Fatima didn’t have a scale at home. But one day she had a gyno appointment, so she brought the pages to the doctor’s office, and when she was waiting in her paper robe for the doctor, she pulled the manuscript out of her bag and weighed it on the scale. It was 3.8 lbs.

3.8 lbs.

[Fatima lingers on that thought. We all linger on it.]

[What is Jonah weighing?]

Knowing the weight of her grief in pounds, Fatima had a revelation that grief could be contained. It could be purged and then revised to make sense, and it could be contained.

[Fatima is looking at me again. Does she want me to stop typing? Is this too personal and I shouldn’t be taking notes? Then why is she talking about it to a bunch of strangers?]

[I stopped writing for a few minutes. She stopped watching me. Now I’m writing again.]

She stood in her paper robe at the doctor’s office, suddenly very proud of her manuscript. It was the first time she thought of it as a novel—an entity separate from herself—because it was outside of her body and her mind now, contained in this 3.8-lb. package. Undertow wasn’t a “book” yet in her mind until that moment. Most days it was a beast she was attacking. Other days it was like a wounded animal she was trying to nurse back to health. But there, in the gyno office, it was all of a sudden a novel.

She was proud of this thing for the first time. But ironically, the person she wanted to call and tell about it?

Her mother.

[My heart is breaking, breaking. It’s broken. I’m shattered. I’m sitting in Witches Brew in tiny little shattered mosaic pieces. I never thought I could love Undertow more than I already did.]

I. Was. Wrong.

Later . . . 11:53 p.m.

Home

Our plan worked again. We lingered behind. Guy-in-red-baseball-cap did the same, but he only thanked Fatima for the discussion and asked her to sign a book and then went on his merry way. I told Fatima that she made me see Undertow in a different light, and that there’s so much more to it than I thought. But then she totally blindsided me, practically whacked me in the head with a brick. She said that she saw me taking copious notes during her talk and she ASKED TO READ THEM!

Complete and total panic! I had quoted her. I had mentioned the way she was staring at me. I had injected my thoughts into her book talk about the most difficult period of her life. I’d commented on her makeup. I wrote about her visit to the gyno! What was I thinking taking notes on that? Why would I even think that it was okay to document that? What else had I written? I couldn’t even remember.

I asked Fatima if I could clean the notes up first; they were a jumbled mess. If I could just clean them up then I would email them to her later. But as that was coming out of my mouth, I knew she was going to say no. Why would she wait on notes from me? And why would she ever give me her email address?

“I’d really like to see them now,” she said. “I’m interested to see what you found most compelling, you were so intense over here, writing everything down. Are you a writer?”

“Not even. But I might want to be,” I said.

“Then I’d really like to read them, from a future writer’s perspective.”

What was I supposed to do? I didn’t have any choice but to show her. I felt like she’d c

aught me cheating on a test and was going to check my answers right in front of me. Miri and Penny were like, Go ahead. Show her. What’s the big deal? Plus, Fatima called me a future writer. So, I sat back down and opened my laptop and I showed her.

I kept thinking Fatima Ro is sitting with me. Fatima Ro is reading my notes. She’s touching my keyboard. She saw my dumbass desktop picture of the movie The Bling Ring. I swear, I like the image as an actual photograph—meaning, its composition and color and use of positive and negative space—not because it’s from The Bling Ring. Okay, I did like the movie on a so-bad-it’s-good level, but that doesn’t mean I’m a Bling Ring person. I wanted to explain all of this to Fatima, but I was too frazzled.

“Thank you.” That was all Fatima said.

Thank you? Was she trying to kill me with awkward? “You’re welcome.”

She stood and stared at me.

I closed my laptop. Damn Bling Ring.

But then she shocked me again. “What are you guys doing right now?”

The only acceptable answer, of course, was “Absolutely nothing.”

“Well,” she said. “The new book I’m planning is set in a private school. I haven’t been to one since I graduated. I would love to see Graham. Will you take me there?”

WHAAAAT????!!!

Penny

Can you tell me about the night you took Fatima to Graham with Miri and Soleil?

Uh-huh. [laughs] Oh, god. I ruined my lace-up flats that night. Nobody else had them yet! I wanted them to be my new look, like, instead of sneakers or flip-flops. I was trying to up my fashion game. And I thought we were going to sit in a café, not run around Graham at ten o’clock at night. Also, it rained a little that morning, so it was muddy, just my luck. [sigh] It was worth it, though, for Fatima. [pause] Or I thought it was, at the time.

You don’t think it was worth it now?

My friend is in the hospital, so no, it wasn’t.

I’m very sorry about Jonah.

[checks phone] I keep checking my texts for news, you know? I’m afraid that if I stop thinking about him, something bad will happen and I’ll miss it.

If anything happens, I’m sure someone will give you a call. Texting is no way to deliver big news.

[puts phone down] Have you spoken to Miri yet?

Yes.

Does she even care about Jonah?

She’s terribly concerned.

I doubt that.

Why’s that?

’Cause she doesn’t care about anyone but Fatima Ro. She only wants Jonah to get better so that Fatima will be off the hook.

That’s a pretty bold statement.

[shrugs]

Miri was that close with Fatima?

For real? She was, like, Fatima’s clone.

What about the rest of you? Tell me more about that night.

[deep breath] Yeah, well, the gate to the courtyard was open, so we went in. It was exciting, like we were breaking and entering, but just the entering. I’d never been at school when I wasn’t supposed to. And I’d never hung out with anyone famous before. Well, Soleil’s older cousin was on My Super Sweet 16. But that’s not Fatima Ro kind of famous. Anyways, we were sneaking into the courtyard, and Soleil and Jonah were doing the Mission Impossible song. [laughs] We felt, like, such a rush, you know? She was Fatima Ro!

Go on.

That night the stars were just, wow, they were so clear. I’ll never forget it. We could see the layers, I mean, the stars at different depths. It was like when I went to the planetarium in elementary school, only real. Fatima got up on one of the tables, she lay right on top of it, and she said, “You have to do this! Come on. Do this! Pick a table.” So, we each picked a table and lay on our backs. That reminded me of the planetarium, too. Have you been?

No.

The chairs recline all the way back.

Oh.

I picked our regular table where we have lunch on nice days. It was wild lying there at night, and with her. I mean, we’d sat at that very table and talked about Fatima Ro almost every day that year, and then all of sudden she was with us, lying on the table and staring at the sky. [pause] It was, like, this crazy-perfect moment. Oh. Except for my shoes. [laughs] Did I tell you they were Stuart Weitzman?

No.

Yeah . . . [sigh] But then Fatima told us the funniest thing. She was at an Amtrak station a few months after she was published, and there was a song playing over the speakers by some old fart—Conway Twitty, she said. An old lady tapped Fatima on the shoulder and whispered that when she was sixteen she fell in love with a boy at the beach club and they made love in her cabana every night while their parents went dancing on the boardwalk, and even all those years later, every time she hears “It’s Only Make Believe” she has an orgasm. [laughs]

[laughs] That’s a great story.

We were dying laughing. I mean, who says that? And how weird was it that we got to hear it from Fatima Ro? Like, we heard Fatima Ro say orgasm.

[laughs] That’s funny.

Uh-huh. But that story changed Fatima’s life because that’s when she developed her theory of human connections.

Human connections?

It’s the idea that we should, like, approach each other with open hearts and reveal our authentic selves through precious truths.

What are precious truths?

Um . . . like the old lady’s cabana story. That woman was a complete stranger, right? But in a few seconds Fatima knew her better than friends she’s had since she was a kid. So, Fatima believes that looking people in the eye and sharing intimate thoughts breaks barriers, makes people fall in love, and can, like, literally end wars.

Huh.

I know it sounds wacky, but it wasn’t. It was Fatima Ro, and we were watching the stars, and it made more sense than anything, like, ever. She was talking about how you can know someone for years but never really know them.

That’s true.

You see? Fatima said that it’s true of neighbors and people who sit next to you in class because your names are alphabetical, but also your own family members. So, I started thinking about Soleil and Miri and me. I mean, we threw, like, the hottest parties on Long Island, we went to Natsumi, we went to Ed Sheeran, we talked about Undertow, but I never felt like part of it, not really. I know what my friends thought of me.

What do you mean?

They thought I was basic, that I was only about clothes and guys and Pretty Little Liars. Since they were into their books and were in honors classes and taking AP Psychology, which was, like, the trendy class to take that only accepted a few juniors a semester, they acted all deep and intellectual. It bothered me—a lot, actually—because I had opinions and goals and things like they did.

Sounds frustrating.

[nods] But while I was listening to Fatima and looking at the sky, I realized something sort of big for me.

What was that?

It was my fault they thought I was an airhead. Like, how were they supposed to know my thoughts if I didn’t tell them? I wasn’t transparent the way Fatima said we should be. I wasn’t living inside/out or offering precious truths. Like, what did I ever do besides style our party outfits and collect the fifty-dollar cover charge at the door?

Fifty dollars? Holy crap!

Well, they were super-exclusive parties. You wouldn’t want just anyone walking into your house, would you?

No, but still. I was thinking more like five bucks.

Do you know how much it costs to rent blackjack tables?

No.

A lot.

Apparently.

[sighs] That night at Graham was the stuff of life. It was the best night since, well, ever. Way better than casino night. But I was complaining about my shoes. Yeah, I was upset about them, but I had revelations and stuff, too. I could’ve talked about that, but I didn’t.

Why didn’t you?

I wanted to. But then better things happened.

Better things?

Jonah started

singing that old Coldplay song, you know, the one about stars? It was nice. He was happy. [pause]

Jonah wasn’t usually happy?

Uh, um . . . I don’t really want to talk about him.

That’s fine. It’s just that you mentioned it.

I just meant that we were all happy.

All right. So what else happened?

We shared being in the universe together.

Hm.

It wasn’t weird.

I didn’t say it was weird.

Fatima said that human connections don’t have to come through precious truths. They can develop through sharing precious experiences, and we were having one by being in the universe together under the stars.

I can see that.

She had shared Undertow with us, and we were sharing the stars with her.

I get it.

Most kids start at the Graham School in ninth grade, right? But me and Soleil and Miri, we’d been there since seventh. I was sorta tired of it. I was dreading that junior year would be the same as every other. I don’t love Graham the way Miri and Soleil love it. I’m not captain of anything like they are. School’s not as easy for me. But that night in the courtyard I knew the year was going to be better; sharing the sky with Fatima Ro was the start of that ’cause I got to do something with my friends that wasn’t shopping or Snapchat, you know? It felt, like . . . important.

Cool.

Yeah. And then you won’t believe what Fatima said next. She said that she felt positive energy from each of us and that she’d moved to Long Island because she wanted to open her life to new friends and new perspectives. She sat up on her table and looked around at us and said, “I want you to be my people.”

Whoa.

For real. [shakes head] Fatima Ro wanted us to be her people.

That was something, huh?

It was everything.

The Absolution of Brady Stevenson

BY FATIMA RO

(excerpt)

When Brady Stevenson moved out of his childhood home, he took his old Coke-bottle glasses but left his wrestling trophies behind. The awards remained as they were for nearly a year—stuffed into the corner of Brady’s closet, along with fallen wire hangers, unmatched socks, and an unopened package of Fruit of the Looms that were a size too small, given to him by his nana, who always thought of him as two years younger than whatever age he happened to be.

All of This Is True

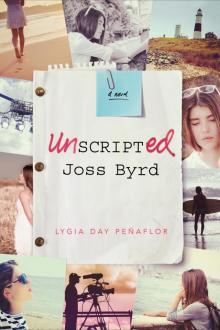

All of This Is True Unscripted Joss Byrd

Unscripted Joss Byrd